A320 / B350, Hayden CO, USA, 2022

A320 / B350, Hayden CO, USA, 2022

Summary

On 22 January 2022, an Airbus A320 departing the uncontrolled airport at Hayden, Colorado, announced its intended runway 10 takeoff despite calls from a Beech King Air 350 that it was inbound to reciprocal runway 28. When the A320 crew subsequently announced they were commencing takeoff from 10, the King Air Pilot responded by asking if the A320 was intending a quick turnout. Almost immediately after confirmation, the A320 captain rotated 24 knots before the correct speed with a resulting tail strike. Once airborne, an evasive right turn was commenced with the reciprocal-direction King Air just over 2 nm away.

Flight Details

Aircraft

Operator

Type of Flight

Public Transport (Passenger)

Flight Origin

Intended Destination

Actual Destination

Take-off Commenced

Yes

Flight Airborne

Yes

Flight Completed

Yes

Phase of Flight

Take Off

Flight Details

Aircraft

Operator

Type of Flight

Private

Flight Origin

Intended Destination

Take-off Commenced

Yes

Flight Airborne

Yes

Flight Completed

Yes

Phase of Flight

Descent

Location - Airport

Airport

General

Tag(s)

En-route Diversion

HF

Tag(s)

Plan Continuation Bias,

Procedural non compliance

LOC

Tag(s)

Aircraft Flight Path Control Error,

Unintended transitory terrain contact

LOS

Tag(s)

Uncontrolled Airspace,

VFR Aircraft Involved

Outcome

Damage or injury

Yes

Aircraft damage

Major

Non-aircraft damage

No

Non-occupant Casualties

No

Off Airport Landing

No

Ditching

No

Causal Factor Group(s)

Group(s)

Aircraft Operation

Safety Recommendation(s)

Group(s)

None Made

Investigation Type

Type

Independent

Description

On 22 January 2022, an Airbus A320 (N760JB) operated by JetBlue Airways on a domestic passenger flight from the uncontrolled airport at Hayden, Colorado, on a flight to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, in day visual meteorological conditions (VMC) began takeoff from runway 10. The crew were unaware that privately operated Beech B350 King Air (N350J), on a flight from Fort Smith, Arkansas, to Hayden was on final approach to the opposite direction runway 28. On realising the situation during the takeoff roll, the Airbus captain immediately rotated at a speed well below the appropriate calculated speed, and a tail strike occurred, causing substantial airframe damage. Once airborne, the A320 immediately turned off the extended runway centreline to avoid the other aircraft. After initially not assessing whether completion of the intended flight was compatible with the tail strike (the occurrence of which was confirmed on request by the cabin crew), the crew continued the climb en route to FL310 until eventual contact with the company maintenance control centre (MCC). MCC advised “landing immediately” at the nearest suitable airport for an aircraft inspection. Denver was selected, with diversion there made without further event.

Investigation

An accident investigation was carried out by the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB). Data from the aircraft digital flight data recorder (DFDR) was provided but ended before arrival at Denver. The quick-access recorder (QAR) and the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) were available, as were recorded radio transmissions and relevant ADS-B data for both aircraft.

It was noted that the 45-year-old captain who was acting as pilot flying (PF) for the sector had been employed as a pilot by the operator for 15 years and since then had logged a total of 11,590 hours flying experience. He had been flying the A320 for 10 years and had been promoted to captain after three years on type. The 40-year-old first officer had been employed as a pilot by the operator for 8 years and since then had logged a total of 3,307 hours flying experience. He had been flying the A320 for six years.

What Happened

Hayden had a single 3,048 metre-long runway 10/28 and a full-length parallel taxiway with the north side terminal building located slightly nearer to the runway 10 threshold than the 28 threshold.

As the A320 left the ramp, its first officer transmitted on the Hayden CTAF (common traffic advisory frequency) that they were “leaving the ramp area to taxi to runway 10 for departure." Almost immediately, the B350, inbound to Hayden from the east, called on the CTAF that they were passing 17,000 feet in descent. The B350 also reported it was "about nine minutes out, for 10, coming in from the east." The CTAF operator responded by stating there were “multiple aircraft inbound," and that the wind was calm. The operator also provided the altimeter setting. After this exchange, the A320 flight crew had a discussion about “the active runway and the multiple inbound airplanes using runway 10." Two minutes after this, the A320 contacted Denver ARTCC to report that they were on the ground at Hayden and would be ready for departure in about 6 or 7 minutes. They were asked if they intended departing from runway 10 and, having confirmed this, were instructed to call back (for a route clearance) when ready for departure.

As the A320 was starting its second engine, the B300 crew had visually acquired Hayden and were cancelling their IFR flight plan with Denver Centre and advising Centre that they intended to land on runway 28. A new squawk was given and the change to Hayden CTAF was approved. The B350 then called on the CTAF that they were “going to go ahead and land 28” and were “straight-in 28 right now." About 10 seconds after this, the A320 called on the CTAF that they were “leaving the ramp area and taxiing to runway 10 for departure." The CTAF operator responded that “multiple airplanes were inbound, and the winds were calm." Whilst the A320 crew was performing the After Start Checklist, the B350 announced that they were “on a 12-mile final 28 straight-in” and about 45 seconds later, the B350 called again asking “if anyone was about to depart from runway 10.” The A320 crew replied that they intended to hold on the (full-length parallel) taxiway near the end of runway 10 whilst awaiting their clearance from Denver Centre. On hearing this, the B350 called to say that they were “on a 10 mile final, 28, straight-in” and the A320 replied “alright, copy” and added that they “would keep an eye out for them”.

About one minute later, the A320 contacted Denver Centre to report they were “ready for departure (from) runway 10," read back the clearance, and immediately called on the CTAF that they had received their clearance and “would be departing on Runway 10." The B300 crew responded that they were “on final 28” and added that they “had been calling." The A320 crew replied on the CTAF that they thought the B350 was 8 or 9 miles out and received a response from the B350 saying that “they were 4 miles out (maybe) even less than that." The A320 pilot monitoring (PM) subsequently stated that “they looked (up the 10 approach) for the airplane both visually and on TCAS and did not see any air traffic,” and so acknowledged the call and announced on CTAF that they were entering runway 10 and beginning their takeoff. The B350 responded by saying that they were on a short final and “I hope you don’t hit us."

ADS-B data showed that when the A320 taxied onto Runway 10, the B350 “was on a reciprocal course 4.91 nm distant." Eleven seconds after the A320 had begun its takeoff acceleration towards calculated V1 and V2 (both 142 KIAS), using takeoff/go-around (TOGA) thrust - and just before the 80-knot cross check - the following exchange between the A320 pilots took place:

- The PM first officer asked the captain if the B350 was on Runway 28

- The captain asked “is he?”

- The PM responded “yes, he is on 28, do you see him?”

- The captain said “no”

(The first officer subsequently explained that early on during the takeoff roll, he had seen traffic dead ahead on the TCAS but had not visually acquired it.)

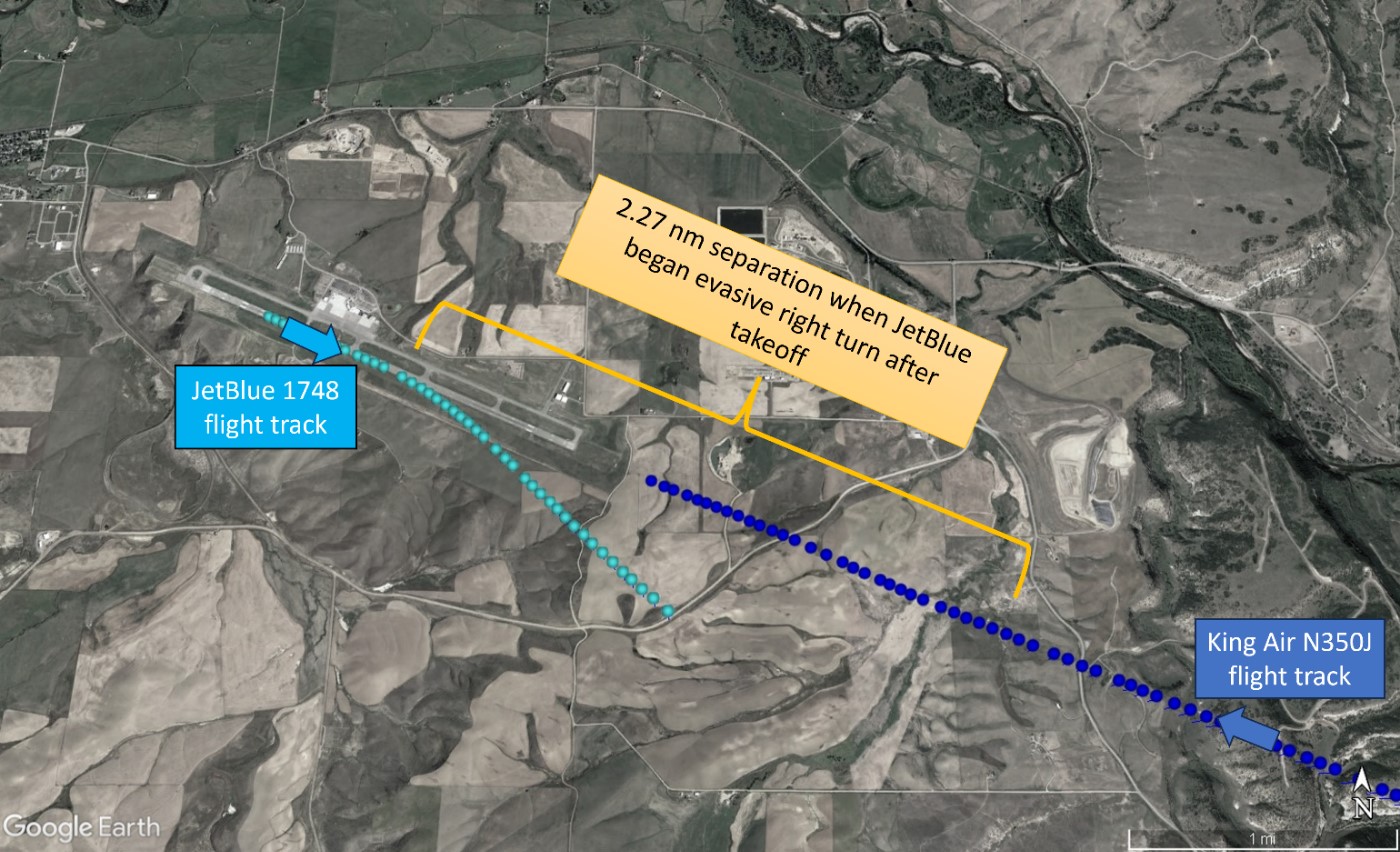

About 20 seconds into the A320 takeoff roll, “the B350 asked the A320 if they were going to do a quick turn-out” to which they replied in the affirmative. As the same time, the A320 captain began rotating the aircraft for takeoff at 118 KCAS - 24 knots before the (correctly calculated) VR based on the aircraft weight - to facilitate airborne avoidance of the opposite-direction B350. Both A320 pilots subsequently stated that they had “never visually acquired the other aircraft." This premature rotation resulted in the aircraft tail striking the runway surface. Immediately on becoming airborne, the captain turned the aircraft to the right, away from the inbound traffic indicated on the TCAS. ADS-B data showed that when the A320 began this right turn, the B350 “was on a reciprocal course with 2.27 nautical miles of separation between the converging airplanes” (see the illustration below).

The collision avoidance deviation by the A320 after becoming airborne. [Reproduced from the Official Report]

Six minutes into the flight, the A320 pilots asked their cabin crew “what they felt in the back of the airplane” and were told the cabin crew had felt a tail strike. By this time, the aircraft was passing 16,000 feet in the climb (approximately 9,400 feet above the elevation of Hayden). On hearing confirmation of the tail strike, the flight crew contacted the airline’s MCC for advice. About five minutes later, passing FL260 and still climbing, they were “recommended” to land as soon as practicable so the aircraft could be inspected for damage. They levelled the aircraft at FL310 and decided to divert to Denver, which was achieved without further event.

The applicable flight crew operating manual (FCOM) procedure for responding to a tail strike was omitted, as was the corresponding quick reference handbook (QRH) procedure. The former stated that “if a tail strike occurs, avoid flying at an altitude that requires pressurizing the cabin and to return to the originating airport for a damage assessment." The QRH procedure for a tail strike was “to land as soon as possible and climb at a maximum of 500 fpm and descend at a maximum rate of 1000 fpm to minimise pressure changes all the while not exceeding 10,000 feet msl or MInimum Safe Altitude (MSA)." However, the flight crew’s delay in recognising that a tail strike had occurred was relevant since both sets of guidance referred to actions “when a tail strike is experienced” rather than when a tail strike is “suspected."

Why It Happened

The A320 pilots both did not realise their departure from an uncontrolled airport was being made in the reciprocal direction of an inbound aircraft. This happened despite the B350 announcing its intention on multiple occasions, which gave multiple opportunities for the A320 pilots to recognise and respond to the potential conflict.

It was noted that pilots on the JetBlue A320 fleet rarely operated to uncontrolled airports -- where traffic separation relies on aircraft announcing intentions in good time and other aircraft paying careful attention and adapting their intentions accordingly.

It was found that FAA Advisory Circular 90-66B (now superseded by AC 90-66C) clearly described the CTAF “self-announce” procedure and that the inbound B350 complied, although it was considered that “the composition of these calls had the potential to be clearer." This AC stated that when transmitting on CTAF, “the correct airport name should be spoken at the beginning and end of each self-announce transmission” to ensure the call is associated with the applicable airport. However, all calls made by the B350 had “omitted identifying the airport at least once at the beginning or end of the transmission and sometimes they completely omitted the airport name."

It was noted that, as in this event, it was “common for pilots to omit the word ‘runway’ when communicating about airport runway numbers,” whereas standard phraseology required the use of the word ‘runway’ followed by the numbers which identify that runway. All the B350’s radio calls had omitted this word when announcing their intention to land on Runway 28, whereas the use of prefix ‘runway’ “would have provided a cue to listen that would have been more difficult to overlook if, as postulated by the Investigation, both A320 pilots had been simultaneously affected by expectation bias”.

It was also noted that the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) procedure for obtaining an en route IFR clearance prior to departing an uncontrolled airport usually involves a short-duration “void time” - in this case it was two minutes. After that time the clearance expires if takeoff does not occur, and if missed, it requires strict procedures to be followed. However, a desire not to exceed the void time must not be allowed to reduce awareness of any relevant CTAF communications.

Finally, it was observed that CTAF operators are not required to communicate with pilots but should they do so, there are no applicable standards. It was considered that the CTAF operator could, instead of transmitting that “multiple airplanes were inbound," have supported traffic deconfliction by including information on already-announced intended runway use when acknowledging potentially conflicting intentions. It was considered that this might have prevented the A320 pilots from erroneously continuing to believe that the B350 was inbound on Runway 10.

The investigation report concluded by noting a fatal 1996 intersecting runway runway collision. This accident had also involved a scheduled service flight and a light aircraft at an uncontrolled airport, and it had also followed a misunderstanding about intended runway use.

The Probable Cause of the accident was found to be “the A320 captain’s rotation of the airplane pitch (attitude) before the rotation speed for takeoff (had been reached) due to his surprise about encountering head-on landing traffic, which resulted in an exceedance of the airplane’s pitch limit and a subsequent tail strike."

Two Contributory Factors were also identified as:

- the A320 flight crew’s expectation bias that the incoming aircraft was landing on the same runway as they were departing from

- the conflicting traffic’s nonstandard use of phraseology when making position calls on the Common Traffic Advisory Frequency

Safety Action taken by JetBlue Airways included its Safety Team working with JetBlue University instructors to develop a training curriculum for flight crew operating to non-towered airports, covering un-annunciated failures and their QRH procedures, and time compression that would be a two-hour brief using as an example the New York JFK to Burlington sector with an arrival or departure after the tower has closed.

The Final Report was published on 13 December 2023. This summary also draws on information contained in the corresponding published Investigation Docket. No safety recommendations were made.