AT72, Belfast International, UK, 2023

AT72, Belfast International, UK, 2023

Summary

On 7 March 2023 an ATR 72-200 crew discovered the rudder was extremely difficult to move during the landing flare, but nosewheel steering was enough to prevent a runway excursion after touchdown. The aircraft was found to have a history of rudder stiffness, which a recent attempt to rectify had not resolved. The crew knew of this and decided that despite a somewhat unsatisfactory preflight rudder check, absence of any significant crosswind component would permit the flight. Investigation attributed stiffness to corroded bearings in the rudder actuation system in the presence of excessive undrained moisture.

Flight Details

Aircraft

Operator

Type of Flight

Public Transport (Cargo)

Flight Origin

Intended Destination

Take-off Commenced

Yes

Flight Airborne

Yes

Flight Completed

Yes

Phase of Flight

Landing

Location - Airport

Airport

General

Tag(s)

PIC less than 500 hours in Command on Type,

Unplanned PF Change less than 1000ft agl

LOC

Tag(s)

Significant Systems or Systems Control Failure

RE

Tag(s)

Directional Control

AW

System(s)

Flight Controls

Contributor(s)

Component Fault in service,

Corrosion/Disbonding/Fatigue

Outcome

Damage or injury

No

Non-aircraft damage

No

Non-occupant Casualties

No

Off Airport Landing

No

Ditching

No

Causal Factor Group(s)

Group(s)

Aircraft Technical

Safety Recommendation(s)

Group(s)

None Made

Investigation Type

Type

Independent

Description

On 7 March 2023 an ATR 72-200 (G-NPTF) operated by West Atlantic on a scheduled domestic cargo flight from East Midlands to Belfast International was in the flare to land at destination in night visual meteorological conditions (VMC) with a small crosswind when the pilots found the rudder extremely difficult to move. The captain took over and ensured the nose landing gear was on the ground ahead of power reduction to flight idle, which ensured early availability of directional control using nosewheel steering to preclude a runway excursion.

Investigation

An investigation was carried out by the UK Air Accident Investigation Branch (AAIB). Recorded data from the flight were recovered from the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) and flight data recorder (FDR). Although the CVR corroborated the flight crew’s recollections, the FDR data were unhelpful because the forces detected by the force detector rod linked to the rudder pedals were not recorded. An option to incorporate this was subsequently introduced but it was not automatically included in all new aircraft FDR capability until the -600 variant was introduced.

The 45-year-old captain had a total of 6,750 hours flying experience, which included 92 hours on type. No age or experience information was given in respect of the first officer, who was acting as pilot flying (PF) for the flight until the inoperative rudder was encountered in the landing flare and the captain took control.

What Happened

The crew took over the aircraft at East Midlands following its arrival there approximately three hours earlier. They and other crews on the fleet were aware that the aircraft had for some time been subject to undue pedal force required to move the rudder and that maintenance action intended to resolve the problem had recently occurred. Once taxiing for departure, the routine check for full and free movement of the flight controls was performed and both pilots found that “the rudder seemed to be very stiff to move”. The first officer was of the view that rudder movement seemed stiffer than other aircraft in the company fleet which he had flown. A brief discussion on whether to continue with the flight including consideration of the lack of significant crosswind component took place. It was decided to continue because the rudder was moveable “albeit with significant effort."

The flight to Belfast was uneventful with the climb reported to have included approximately 15 minutes in cloud and icing conditions before emerging into clear skies. An ILS approach to runway 25 was flown with the autopilot (AP) disconnected at 700 feet aal. The first officer recalled that “as he flared the aircraft for landing, what little wind there was (equivalent to a crosswind component of less than 5 knots) started to cause the aircraft to drift very slightly to the left of the centreline” and on attempting to compensate for this, he had found the rudder pedals “almost impossible to move." The captain recognised the problem, took control for touchdown, and rapidly de-rotated the nosewheel to allow use of nosewheel steering.

Once down to taxi speed, both pilots attempted to move the rudder pedals and found that they could barely be moved. Following arrival on the allocated stand and the unloading of all the cargo, the aircraft was positioned to a remote stand and the flight crew found that the rudder pedals could not be moved at all.

The investigation noted that the flight crew operating manual (FCOM) required that the preflight ‘full and free’ check of the controls in respect of the rudder required that the left seat pilot must “move the rudder pedals to full travel in both directions and verify freedom of movement." It was also noted that the FCOM Abnormal Procedure for in-flight rudder jam included a requirement to put the nose down at touchdown “before reduction of power below flight idle as the Captain had done."

It was also noted that three defect entries concerning stiffness in rudder pedal movement had been recorded over a five-day period during the month prior to the event under investigation. These had culminated in the aircraft being grounded for 10 days and, with substantial trouble shooting assistance from ATR, three rudder actuation components being replaced. The aircraft had then been in service over a period of 15 days prior to the landing at Belfast.

Why It Happened

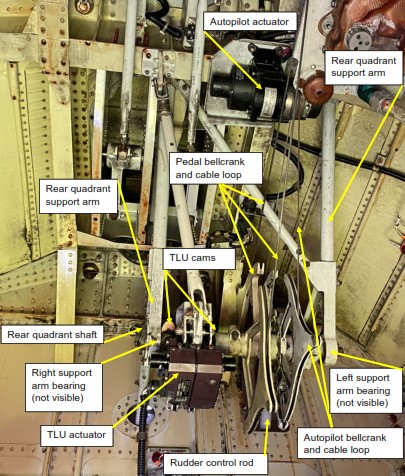

An initial examination of the aircraft confirmed that the rudder was extremely difficult to move both using the pedals and by hand on the rudder surface. The pedals were also found not to return to neutral after being moved, and the rudder surface “did not appear to move in response to external wind inputs." The bay where the rudder rear quadrant (see the annotated illustration below) was located appeared to be dry, and there was no evidence that either moisture or ice had accumulated there. A further detailed examination of the quadrant initially found nothing of likely relevance. However, it was then noted that when the rudder control rod was disconnected at the rear quadrant shaft to isolate the rudder pedal circuit from the actuation circuit, “considerable stiffness remained within the pedal circuit,” although this appeared to be less than before disconnection.

The rudder rear quadrant looking aft. [Reproduced from the Official Report]

The rudder pedal circuit pulleys and cables were found to be clean and free of debris but without any evidence of recent lubrication, and both the AP and rudder pedal cable tensions were “within, or very close to, the normal range”. After the aircraft had been moved to a hangar, a more detailed examination with assistance from ATR flight control and structural specialists was carried out. Various potentially contributory factors which would have collectively contributed to rudder stiffness in either the command/rudder pedal circuit or the actuation/rudder circuit were examined. As a result, further attention was then focused on the actuation/rudder circuit.

It was found that after disconnection of both sides of the rudder system, “the rudder pedals remained very difficult to move.” However, when the rudder pedal and autopilot yaw cables were disconnected from their respective bellcranks, “it was then possible to operate the rudder pedal cables freely using only finger pressure” with the rudder pedals moving freely in response, which confirmed that the friction had originated at the rear quadrant shaft. Also, it was found that resistance to movement in the actuation/rudder circuit was only completely eliminated when the rudder damper was removed, which confirmed that the rudder damper installation had been a contributor to stiffness in the rudder operating circuit.

Further examination of the two rear quadrant support arm bearings, which were of a design replaced in subsequent manufactured aircraft, found that one did not readily rotate although it was fully greased. The other was completely seized and ungreased despite being a sealed bearing. The outer ring of the latter bearing was found to be axially misaligned. Closer examination of the rear quadrant after removal and mounting in a test rig then found that the Travel Limit Unit (TLU) pivoting bracket rollers were seized and had clearly “not turned for some time." As a result of the findings made, the ATR declared the rear quadrant shaft and its associated components unserviceable.

It was noted that at the time of the event under investigation, “there were no prescribed maintenance procedures or inspections specifically relating to the bearings on the rear quadrant shaft.” However, a detailed visual inspection (DVI) of the rudder control cable circuit is required every eight years and had been performed during the troubleshooting with the aircraft rudder system earlier in the month with ATR stating that “this inspection should be able to detect friction in the rear quadrant support bearings." However, it was noted that in 1993, ATR had issued an SB 72-27-1020, which allowed replacement of the steel bearings installed at build with a corrosion-resistant alternative. But this was not made mandatory and was not actioned on the aircraft under investigation and “many other aircraft with the same unmodified rudder operating circuit had continued to operate with similar issues."

This led the Investigation to conclude that “the presence of excessive moisture in the rear bay (had) undoubtedly contributed to the corrosion on the bearings." Whilst it was recognised the rear bay where the corroded bearings were found was not intended to be a fully sealed area and some moisture could be expected, this would not normally occur to the extent observed and could only have taken place because of excessive moisture ingress.

It was recognised that one explanation in addition to rainwater penetration could well have been frequent preflight ground de-icing when “pressurised jets are sometimes used to ensure de-icing fluid reaches the upper part of the rudder” with ATR advising awareness of de-icing fluid residue sometimes being found in the rear bay of other aircraft in the past. This possibility was supported by the fact that some accumulated moisture found in the tailcone during the investigation had “a gel-like consistency, visually consistent with a mixture of water and glycol-based de-icing fluid." Such accumulations had been more likely because one of the two rear bay drain holes was found to be missing, with an additional fastener hole having been added instead of the drain hole at an undetermined point and routine inspections not detecting this. It was considered that such a blockage may not have been found if such routine inspections were performed with the rear bay door in the open position. With only one functioning drain hole, accumulated water and/or de-icing fluid would have then been unable to effectively drain and thus “have created an environment conducive to corrosion." An additional and potentially relevant finding was evidence that all flight control pivot points had been lubricated alternately with a different grease, which was “not intended to occur” and would have compromised the effectiveness of this regular lubrication.

The formal narrative Conclusion of the Investigation was recorded as follows:

Following an extensive history of reports of stiffness within the rudder control system, the flight crew experienced rudder stiffness during the full and free control check prior to the flight. Aware of the recent maintenance interventions which were considered to have resolved the problem, the flight crew elected to continue with the flight. They subsequently encountered excessive rudder stiffness during the landing flare which rendered the rudder pedals almost immovable.

Two support bearings on the rudder rear quadrant shaft were found to be corroded. Trapped moisture in the aircraft’s rear bay probably contributed to the condition of the bearings. Unable to rotate freely, the bearings would have resisted the movement of the rudder rear quadrant shaft leading to the stiffness. Other anomalies observed in the rudder control system may have contributed to the stiffness, but to a lesser extent.

A Service Bulletin published in 1993 existed to replace the affected bearings with corrosion-resistant equivalents, but had not been embodied on G-NPTF. In February 2024 the manufacturer updated the IPC to allow interchangeability for some flight control bearings (including those on the rudder rear quadrant) with corrosion-resistant bearings, as an alternative to the Service Bulletin.

The manufacturer will also issue an operator communication emphasising existing operational and maintenance procedures to prevent reoccurrence.

Safety Action was noted as having been taken as a result of the findings of the Investigation as follows:

- ATR amended the figure referenced in the aircraft maintenance manual (AMM) tasks for removal/installation of the rudder damper, to include an orientation arrow in January 2024.

- ATR took steps to ease the installation of some post-mod flight control bearings, including the rudder rear quadrant bearings, so that they can be replaced on an on-condition/opportunity basis, without the need to embody the entire content of SB 72-27-1020 effective in January 2024.

- ATR has also begun a review of the visual inspection tasks applicable to the rudder mechanical control and rudder cable circuit.

- West Atlantic resealed all gaps and areas of degraded sealant on G-NPTF’s vertical stabiliser and their Continuing Airworthiness Management Organisation (CAMO) issued instructions to specify Aeroshell 33 as the only grease to be used for lubrication of the flight control pivot points to ensure a consistent lubrication philosophy and avoid mixing different products and took the necessary steps to ensure that a sub contractor which undertakes some CAMO services was directed accordingly.

The Final Report was published on 28 November 2024. No safety recommendations were made.