B738, Nantes, France, 2022

B738, Nantes, France, 2022

Summary

On 1 October 2022, a Boeing 737-800 first officer undergoing routine supervised training mishandled the touchdown at Nantes. The aircraft sustained substantial damage but there were no injuries. The potential consequences of an inexperienced first officer still undergoing line training attempting to land on the nonstandard runway profile at Nantes with little related coaching from the training captain were underestimated. The aircraft operator enhanced its management of line training, and a safety recommendation to improve operator awareness of Nantes’ nonstandard runway profile was made.

Flight Details

Aircraft

Operator

Type of Flight

Public Transport (Passenger)

Flight Origin

Intended Destination

Take-off Commenced

Yes

Flight Airborne

Yes

Flight Completed

Yes

Phase of Flight

Landing

Location - Airport

Airport

General

Tag(s)

Copilot less than 500 hours on Type,

Flight Crew Training,

Inadequate Aircraft Operator Procedures,

Landing Flare Difficulty

HF

Tag(s)

Inappropriate crew response - skills deficiency,

Manual Handling,

Procedural non compliance,

Ineffective Monitoring - SIC as PF,

Pilot Startle Response

LOC

Tag(s)

Flight Management Error,

Hard landing

Outcome

Damage or injury

Yes

Aircraft damage

Major

Non-aircraft damage

No

Non-occupant Casualties

No

Off Airport Landing

No

Ditching

No

Causal Factor Group(s)

Group(s)

Aircraft Operation

Safety Recommendation(s)

Group(s)

Airport Management

Investigation Type

Type

Independent

Description

On 1 October 2022, the touchdown of a Boeing 737-800 (F-GZHA) operated by Transavia France on a scheduled international passenger flight from Djerba, Tunisia, to Nantes, France, as TO3943 in day instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) and used for first officer line training was mismanaged by the trainee. As a consequence of a hard touchdown on an upward sloping area of the runway, both nose and main gear impact with the runway was hard. Nose landing gear impact, which resulted in both its tyres separating from their rims, was assessed to have been in excess of 6g. A second and final hard touchdown followed. The captain took control and taxied clear of the runway before stopping for disembarkation due to substantial damage to the aircraft including distortion of its airframe.

Investigation

An accident investigation was carried out by the French Civil Aviation Accident Investigation Agency, the BEA, aided by cockpit voice recorder (CVR) and flight data recorder (FDR) data and crew statements.

The 54-year-old training captain in command had 13,075 hours flying experience, which included 7,904 hours on type. He had been appointed as a training captain three years prior to the accident and in recent months had regularly been assigned to oversee line training flights. Although he was based at Paris Orly, he lived in the Nantes area and was regularly rostered for flights from there. The report also said he had a good knowledge of the approach flown prior to the accident and that he was familiar with the runway features.

The 34-year-old trainee first officer had a total of 448 hours flying experience, of which 63 hours had been on type as he worked toward becoming a qualified first officer on his first multi-crew and large multi-engine aircraft type. His licence required the wearing of vision correction. The day before the accident flight, he had resumed training after a three-month break with four sectors of familiarization flights. The final of these flights had involved him acting as pilot flying (PF) for the same approach and landing as the accident flight, although the cloud base was higher than for the accident landing. He added that the ‘hump’ on runway 21 had "disturbed him during the approach” the previous day and the (same) training captain remarked that the touchdown had been “a bit hard and the flare a little late."

What Happened

The first two planned sectors (legs) on the day of the accident were Nantes to Djerba and back. During the cruise on the return flight, the PF first officer “spoke to the captain about his lack of confidence about landing and specified that he did not want to repeat the same landing as the previous day at Nantes, during which the normal load factor had reached 1.7 g." The captain responded by reminding him that his landing at Djerba with a 30-knot crosswind component had occurred without any problems. As the aircraft began descent, the crew started their approach briefing. They noted that the nonprecision required navigation performance (RNP) approach to runway 21 was likely to take place with a significantly lower cloudbase (around 700 feet aal) than the same approach the day before. In particular, they mentioned the offset (13°) procedure approach track and the 'hump' on runway 21 as threats on approach and landing. The CVR showed that “the crew did not mention any strategy as regards the conduct of the approach and the use of automated systems” after discussing those factors the previous day.

With about half an hour to go, the captain noted from the latest automatic terminal information service (ATIS) that although the crosswind was not a concern, the visibility had reduced to 4,800 metres and the cloudbase was 600 feet with light rain and mist. On being informed of this, the first officer remarked that the runway would only be visible “at the last minute." After checking with the first officer, the captain decided that even without the normal simultaneous lead-in-strobe lights on each side of the runway threshold, the first officer could continue as PF for the remainder of the flight.

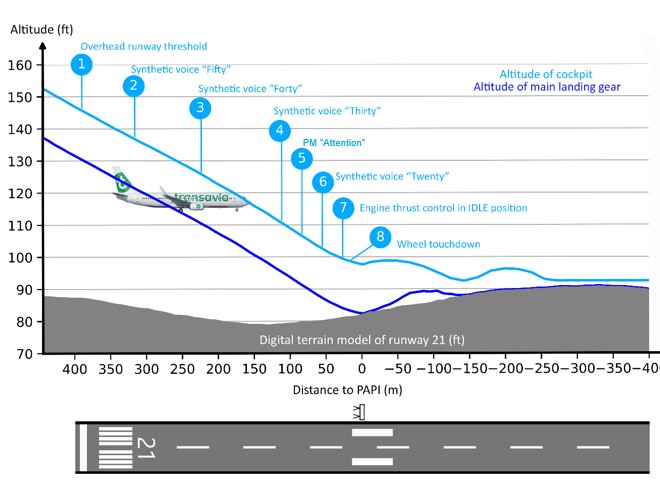

Shortly after passing 2,500 feet agl, the first officer stated he would fly the aeroplane manually from 2,000 feet as he had on the previous day’s flight, “for training purposes,” given the interruption to his training. He then disengaged the autopilot (AP) and autothrottles (AT). On calling four nm to go, a landing clearance was received and just over a minute later, the first officer made the required “stabilised” call as 1,000 feet agl was passed. About one minute later, the instructor called out “runway” while the aeroplane was at approximately 800 ft and two nm from the runway threshold. With about 1.3 nm to go and the approach procedure minimum altitude imminent, the first officer turned the aircraft to align with the runway. The extended centreline track was then held with a drift correction of less than five degrees, and the aircraft remained stabilised with the speed close to the calculated VAPP. Below 500 feet, the captain prompted the first officer to apply corrections to maintain the runway centreline. This was achieved and speed deviations remained small. The runway threshold was crossed at 50 feet agl with the recorded airspeed just two knots above VAPP and decreasing (position one on the illustration below).

The vertical profile of the touchdown. [Reproduced from the Official Report]

Thereafter, as touchdown neared, the first officer applied small nose-up inputs which he began to increase at the 40-feet auto callout (position three). He then increased this “considerably” when approximately 110 metres from the beginning of the touchdown zone (TDZ) whilst leaving the thrust unchanged. Shortly after the 30-feet auto callout, (position four), the captain called out “attention” which resulted in further slight increases in pitch attitude from around 0°. Shortly after 20-feet auto-callout (position six) the first officer set the thrust levers to idle. Main gear touchdown (and consequent spoiler deployment) occurred within the TDZ on the upward-sloping part of the runway at a pitch attitude of approximately 5° (position eight) with a 2.95g acceleration rate. Thrust was still close to 50% - not much less than on the approach - but was continuing to decrease. The aircraft bounced, and then the right and nose landing gear contacted the runway with a recorded normal load factor of nearly 2.2g with the aircraft still on the upward-sloping part of the runway (a gradient of around 1.32%). Both nose tyres burst and separated from their rims (see the illustration below).

The ruptured wheels of nose landing gear. [Reproduced from the Official Report]

Both pilots’ reported having been surprised by the violent initial contact with the runway. It was found from recorded data that when the aircraft bounced, the captain “instinctively made a nose-down input of about three quarters of the maximum possible deflection for less than a second” without announcing his intervention to the first officer. A second and final runway contact followed with the left main landing gear being the last to make contact. As soon as the aircraft was on the ground again, the captain made “another nose-down input, this time to full deflection” whilst the first officer deployed the thrust reversers. As the aircraft continued to decelerate on centreline, the controller informed the crew that both nose gear tyres had been shed on contact with the runway as result of what was later estimated as a 6.5g force. Concurrently, the CVR was recording “a loud and unusual noise." A few seconds later, the captain vacated the runway by turning the aircraft left onto taxiway ‘B.' Having checked that no passengers or crew had been injured, passenger disembarkation was subsequently organised onto ground transport using both the front and rear aircraft doors.

A structural damage assessment found that the nose landing gear wheel rims had failed between the bead seating area and the rim flanges, which were then ejected as the aircraft decelerated. The nose landing gear itself was damaged and both its casing and the airframe in line with the nose landing gear were distorted. In addition, impact damage to both the airframe and engine fan blades was found, which it was considered had been “very probably caused by parts of the wheels and tyres when they detached."

Why It Happened

The Investigation identified a number of contexts which together were likely to have made the accident more likely:

- Although the captain involved was, through familiarity with the airport, accustomed to the challenge presented by a TDZ with a rising slope, he appeared not to recognize that the situation was not ideal for line training of an inexperienced trainee first officer. Transavia had not drawn up specific instructions regarding the selection of destinations during line training flights, nor was there any guidance to help training captains decide whether they allow trainee first officers to perform the approach and landing at particular airports.

- The first officer’s training had been repeatedly interrupted. The investigation found that the first officer had joined the Air France/Transavia group Cadet Training Programme in 2019 having just upgraded his PPL to a commercial pilot licence (CPL) (but without an instrument rating). He had then attended a series of courses over a 14-month period which led to him gaining a multi-engine aircraft instrument rating (IR) and a multi-crew cooperation rating (MCC). His training was then interrupted for 11 months until he began training for his first aircraft type rating (737) in October 2021, which he obtained in January 2022. After a break of just over three months, he then completed base training checks, and after another three-month break finally commenced supervised line training in May 2022. After completing about 20 flights, he was put on sick leave for two months from 23 June 2022 and did not resume line training until 30 September 2022, the day before the accident.

- The unusual longitudinal profile of Nantes runway 21 made it unsuitable for landings by trainee first officers. There was no information in the Boeing flight crew training manual (FCTM) on landing on a runway with an upward slope. It was noted that “the assessment of height and distances when in flight is based on geometric references acquired through experience” and that “a runway with an upward or downward slope therefore modifies the way dimensions of the runway usually appear when observed from a 3° angle." It was also noted that such an upward-sloping TDZ can give the illusion that an aircraft is higher in the flare than it actually is so “it is often recommended to start the flare earlier." The potential consequences of such upward slopes were also identified as possibly affecting radar altimeter height callouts, which could result in late initiation of the flare.

- The longitudinal profile of the Nantes runway did not satisfy the relevant runway certification specifications in three respects. These included that the maximum longitudinal slope of runway 21 is 1.25% on a section in the first quarter of the runway, which is higher than the slope specified in the runway certification requirements (a maximum slope of 0.8%). The state safety regulator had accepted mitigations submitted by the airport operator, but it was found that no reference to this issue appeared in the aeronautical information publication (AIP) entry for Nantes.

- Transavia flight data monitoring (FDM) detected hard landings, and the data showed that most of them occurred on runways with an upward slope. An analysis of a 10½ month period in 2022 found that 25% of such landings occurred during line training sectors. The same analysis found that Nantes and one other airport had recorded almost a third of the total hard landings but that whilst Nantes was classified in the OM-C as a Category ‘B’ airport, the other airport was classified as a Category ‘B-q’ airport with the “-q” extension meaning that minimum crew experience was required.

A number of Potential Contributory Factors in respect of the hard landing and (separately) the damage it caused were documented at the conclusion of the investigation as follows:

The Hard Landing:

- The first officer’s inappropriate actions to increase the pitch attitude and reduce thrust during the flare manoeuvre.

- The workload induced by an early disconnection of the automated systems in adverse weather conditions and at an airport with an offset final approach track, leading to an alignment at a late stage on final approach, at an altitude below 1,000 feet agl and close to minima.

- The absence of a framework or decision-making aid for the airline’s training captains to help them assess whether the difficulty of a flight is consistent with the level of the trainee first officer performing the flight as PF.

- A failure by the airline, on the day of the accident, to take into account the specific features of certain airports when planning flights which will be used for first officer line training.

- Insufficient consideration given by the airline and their captain to the first officer’s fragmented training and recent experience of line training.

- Insufficient consideration given by the captain as to how difficult it could be for the first officer to carry out the approach to runway 21 in the conditions of the day.

- An approach briefing that identified the threats but did not mention the means to mitigate their effects.

- An erroneous perception of the final part of the approach slope due to the upward slope of the runway.

- The training captain’s failure to anticipate the case for taking over the controls during a dynamic flight phase.

The Aircraft Damage:

- Transavia pilots having excessive and ill-proportioned awareness of the risk of a tail strike compared with the risk of a hard landing.

- Insufficient training for actions to be taken in the event of a bounce, which led the training captain in command to react instinctively by applying the inputs specified to avoid a tail strike (and act) without calling that he was taking control.

Safety Action taken by Transavia

Several measures were implemented aimed mainly at improving the progress and monitoring of pilots undergoing line training with respect to destinations that can present certain challenges. These measures were also designed to help training captains better understand their role by providing them with a framework for adapting strategy for different contexts encountered during training flights and critical phases of a flight. In summary, these were as follows:

- withdrawal of destinations with specific features considered to be complex from duty rosters for First Officer line training

- emphasising flexibility in the allocation of the PF and PM roles between s trainee first officer and the training captain in command according to the destination and any context-related difficulties (complex approach, adverse weather conditions, etc.);

- the introduction of standardised instruction in landing technique;

- the introduction of training in the actions to take in the event of a bounced landing;

- the provision of guidance to training captains on taking the controls and formalising this action during the flight;

- pilot training to raise awareness of the risk of a hard landing in comparison to a tail strike.

One Safety Recommendation was made based on the findings of the Investigation as follows:

- that the Nantes Airport Operator (Vinci) should, in coordination with the Aeronautical Information Service (AIS), ensure that the non-conformities identified for the runway 21 approach and the runway itself are included in the French Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP). [FRAN-2024-0019]

The Final Report was simultaneously published in the definitive French language and in a courtesy English Language translation version on 31 January 2025.