DH8D / Vehicles, Calgary, Canada, 2023

DH8D / Vehicles, Calgary, Canada, 2023

Summary

On 6 October 2023, two airside tugs travelling together at Calgary were given a clearance by the ground controller which they misinterpreted as including permission to enter an active runway. On seeing vehicles ahead, the captain of a departing aircraft already at high speed judged that continuing the takeoff was the best option, and the tugs were cleared by a little over 300 feet. The lead driver said he believed that had he misunderstood the route, the controller would have informed him. Driver error was attributed to ‘procedural drift’ and an absence of both recurrent training and effective oversight.

Flight Details

Aircraft

Operator

Type of Flight

Public Transport (Passenger)

Flight Origin

Take-off Commenced

Yes

Flight Airborne

No

Flight Completed

Yes

Phase of Flight

Take Off

Location - Airport

Airport

HF

Tag(s)

Authority Gradient,

Procedural non compliance

GND

Tag(s)

Aircraft / Vehicle conflict,

Accepted ATC clearance not followed

RI

Tag(s)

Accepted ATC Clearance not followed,

Incursion pre Take off,

Runway Crossing,

Vehicle Incursion

Outcome

Damage or injury

No

Non-aircraft damage

No

Non-occupant Casualties

No

Off Airport Landing

No

Ditching

No

Causal Factor Group(s)

Group(s)

Airport Operation

Safety Recommendation(s)

Group(s)

Air Traffic Management

Investigation Type

Type

Independent

Description

On 6 October 2023, a De Havilland DHC8-400 (C-GGNZ) operated by Jazz Aviation on a scheduled passenger flight from Calgary to an unrecorded destination as JZA7124 was on its takeoff roll on runway 17R in day visual conditions (VMC). The aircraft was approaching V1 when the flight crew saw two aircraft tow vehicles entering the runway ahead. The safest response was assessed as continuing the takeoff, and the aircraft completed the takeoff and cleared the vehicles by a little more than 300 feet.

Investigation

An investigation was carried out by the Canadian Transportation Safety Board (TSB). Since sufficient recorded air traffic control (ATC) data were available, it was determined it was unnecessary to download the aircraft digital flight data recorder (DFDR), cockpit voice recorder (CVR) or quick-access recorder (QAR) data. In any case, relevant data on the two-hour CVR had already been overwritten.

The tower controller on duty at the time had 19 years experience, and all but four years had been at Calgary. He had been on duty for two hours and had just returned from his first break. The ground controller had nine years experience, of which three years had been at Calgary and had just begun his shift. He had been on duty for 15 minutes.

The lead tug driver held an Airside Vehicle Operator Permit which was valid for five years and had just over two years to run until expiry. This permit included permission to tow aircraft and to operate on controlled runways and taxiways. The second tug driver also held an Airside Vehicle Operator Permit which was valid for five years and had just over three years to run until expiry. This permit did not include authority to operate on controlled areas of the airport. The holder was therefore required to follow the lead tug at all times. This second tug was equipped with a radio but its driver did not communicate directly with ATC.

What Happened

Runways 17L and 17R were in use, and to allow the planned installation of a software update, the advanced surface movement guidance and control system (A-SMGCS) had been shut down for an expected time of about 30 minutes. To simplify ground movements, runway 17L was used for landings only and 17R for both landings and takeoffs, and increased spacing was applied to ground movements.

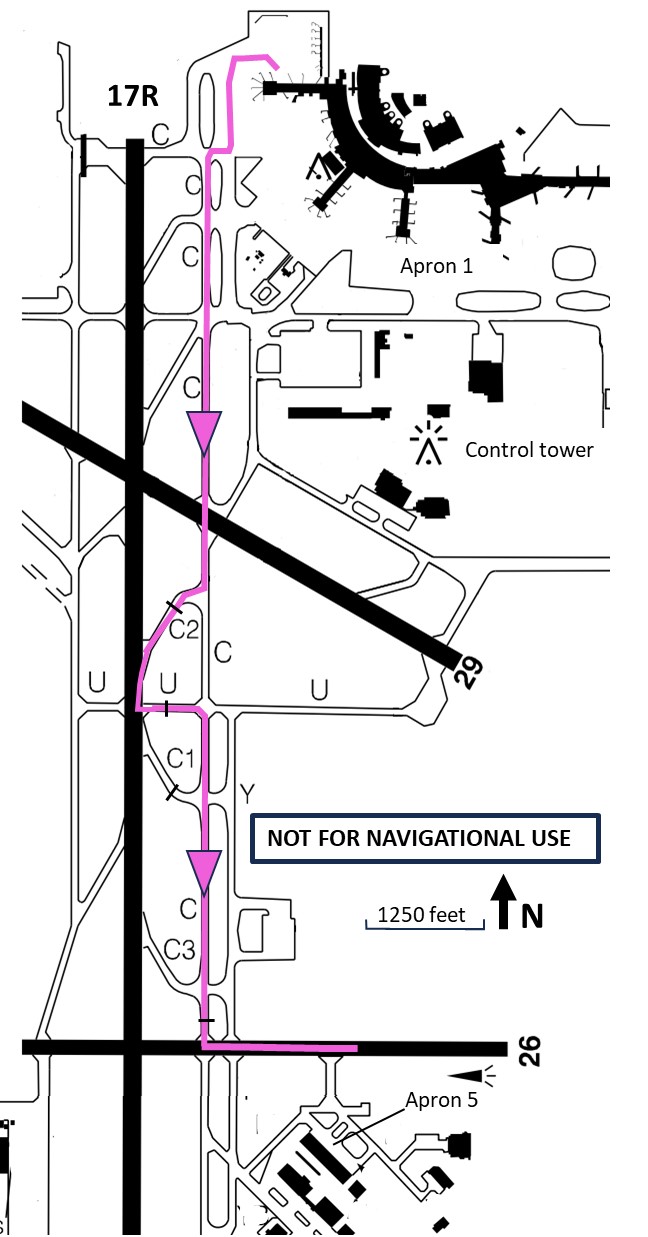

The two tugs had called ground to request transit to closed runway 26 to move an aircraft parked on the part of that runway east of its intersection with runway 17R. The lead tug driver was cleared to taxi south on taxiways ‘C’, ‘C1’ and ‘Y’ and hold short of runway 26 (see the illustration below). A DHC8-400 that had recently landed on runway 17R had exited the runway using a rapid-exit taxiway (RET) and had begun taxiing north on taxiway C towards the passenger terminal. Because taxiway line painting was under way on taxiway U between taxiway C and runway 29, taxiway Y was inaccessible to aircraft. As a result, the ground controller changed his clearance to the two tugs and instructed them to give way to this aircraft by moving onto Taxiway C2 and then holding short of runway 17R whilst remaining clear of taxiway C. The lead tug driver requested clarification of this new instruction and on receipt correctly read it back. Almost immediately, a DHC8-400 about to depart requested taxi clearance from ground and was instructed to taxi from Apron 1 and hold short of the full length of runway 17R.

The relevant aerodrome layout showing the route eventually taken by the two tugs in mauve. [Reproduced from the Official Report]

Around this time, the tugs had entered taxiway C2 to give way to flight JZA133, which was traveling north on Taxiway C. The tugs stopped on the centreline, just short of the runway 17R holding position. Once the inbound aircraft on taxiway C was north of taxiway C2, the two tugs were instructed by ground “to proceed onto Taxiway C and hold short of Runway 26”, which the lead aircraft tug driver read back as given. At approximately this time, the departing aircraft, which had been holding short of Runway 17R, was instructed by tower to line up and wait on that runway. A takeoff clearance followed almost immediately.

The lead tug driver “had never turned around on a taxiway before and believed this was not allowed. In the absence of an explicit instruction to turn around in the ground controller’s last communication, he also believed that doing so on taxiway C2 to join taxiway C would not be possible” given the turning radius of the tugs. He also considered that backing up was not an option “because it would have required both drivers to exit their vehicles” and disconnect the tow bar from the second tug and coordinate movement of the two tugs. The lead driver decided to drive ahead onto the runway in order to make an immediate left turn onto taxiway ‘U’ (see the route taken on the illustration above).

Four seconds after the departing DHC8-400 had been given takeoff clearance by tower, the two tugs began to cross the runway holding position on taxiway C2 and continued onto the runway. The lead tug driver subsequently stated that he had assumed that if this was an incorrect action, the GND controller would intervene and stop him. Sixteen seconds after being given takeoff clearance, the DHC8-400 began its takeoff roll and fourteen seconds after that, the ground controller saw that the tugs were on the runway ahead of the aircraft. As he was busy, he immediately asked the tower controller to “abort the aircraft’s takeoff." The tower controller responded by issuing an “abort” instruction using nonstandard wording. The flight crew subsequently stated that they did not recollect hearing any such transmission and only recognised the conflict ahead when they saw it a few seconds later. By this time they were close to V1 and decided the safest response was to continue and become airborne approximately 1,100 metres before reaching the tugs. The aircraft passed over them with a clearance in excess of 300 feet.

Why It Happened

The reasons for conflict included a combination of inadequate training and oversight for the lead tug driver and the resulting "procedural drift." The investigation also noted differing mental models of the situation held by the ground controller and the lead tug driver, and the existence of an authority gradient between controllers and ground vehicle operators.

Airport authority drivers' permits had - crucially - no recency or recurrent training requirements within their five-year validity period. The authority’s ‘Airside Traffic Directives,’ which constitute the basis for airside driver training require that vehicles leave enough room to turn around on a taxiway if required. However, the investigation considered that this requirement was likely to be rarely used and thus lost by “procedural adaptation” over time since, in most cases, the controller will instruct a driver to continue in the established direction. It was considered that this requirement was “also an example of a procedure that was written in a general sense and required interpretation on the part of the driver to know what constituted enough room based on the vehicle they were driving." Without adequate and regular driver proficiency checks, it was considered that it would be easy for procedural adaptations to go unidentified and uncorrected.

Regarding the tug driver's decision to enter the runway rather than seek confirmation of what the ground controller expected, it was noted that “an instruction to hold short of a runway is almost always followed by an instruction to continue on that route onto the runway and not to turn around." It was also noted that the lead tug driver had never turned around on a taxiway even without the complications of a second tug and a tow bar and “believed this was not allowed." He also thought it might not have been possible to turn through 180° on the 27-metre-wide taxiway from his taxiway centreline position, given the tug’s 12-metre steering radius in two-wheel steering mode. The report also noted the steep authority gradient between vehicle drivers and air traffic controllers. It further noted that, amid that authority gradient, driver training did not address interaction between vehicle drivers and controllers beyond guidance to use the phrase “say again” if in doubt about an instruction.

It was also considered that there is value in both controllers and drivers learning about the practices that each use for both to communicate with each other to best effect. It was noted that whilst the Calgary Airport Authority “does conduct frequent outreach activities with NAV CANADA to facilitate this kind of information sharing," vehicle operators did not have this opportunity. That's because their employee safety management activities were the responsibility of the airlines they worked for rather than the Airport Authority.

The investigation also reviewed the mitigation used for temporary operation without the availability of A-SMGCS and considered that the existing procedures “might not be enough to sufficiently reduce any risk and other strategies, such as staffing an additional controller position, may need to be employed."

Finally, although it was accepted that it was impossible to determine what would have happened had the prescribed phraseology been used by the controller when he attempted to get the takeoff rejected, “what was said was ineffective as neither flight crew member recalled hearing the instruction, it could not be determined why the controller did not use the current phraseology."

The Findings of the Investigation were formally documented as follows:

Causes and Contributing Factors

- Due to procedural drift over time from an absence of recurrent training and oversight, the lead tug driver stopped too close to the Taxiway C2 runway holding position marking, which did not leave enough room for the vehicle to turn around as required by the applicable Airside Traffic Directives.

- The ground controller’s mental model was that the lead tug driver would continue the route the controller had instructed. This was contradictory to the lead tug driver’s mental model in which the only way to continue the route was to enter Runway 17R; this mental model had been shaped, in part, by his proximity to the runway holding position. Consequently, the driver misinterpreted the instructions of the ground controller and entered Runway 17R while the departing aircraft was beginning its takeoff roll, resulting in a risk of collision.

Risk Factors (defined by the TSB as “factors that were found to pose a risk to the transportation system which may or may not have been causal or contributory to the occurrence but could pose a risk in the future”)

- If the authority gradient between an air traffic controller and a ground vehicle operator is not proactively managed, a ground vehicle operator may not feel comfortable asking for clarification if he or she considers an instruction to be unclear or erroneous. This could potentially result in an operator taking actions that differ from those intended by an air traffic controller.

- If NAV CANADA relies primarily on additional time and aircraft spacing when A-SMGCS is disabled and key safety features are unavailable, there is an increased risk that hazardous situations such as runway incursions will occur and be detected too late to recover the situation.

- If air traffic controllers do not use the correct phraseology for safety-critical situations, there is a risk that the consequences of these situations could be more severe.

One Safety Recommendation was issued based on the Findings of the Investigation as follows

- that NAV CANADA amend its phraseology guidance so that safety-critical transmissions issued to address recognized conflicts, such as those instructing aircraft to abort takeoff or pull up and go around, are sufficiently compelling to attract the flight crew’s attention, particularly during periods of high workload. [Recommendation A18-04]

(This Recommendation was issued prior to the completion of the Final Report and the corresponding phraseology had already been amended prior to its completion and it has already been closed as the action taken was deemed as “fully satisfactory.")

The Final Report of the Investigation was authorised for release on 4 June 2025 and officially released on 22 July 2025. No Further Safety Recommendations were made.