S92, en-route, southwest of Stavanger Norway, 2020

S92, en-route, southwest of Stavanger Norway, 2020

Summary

On 20 October 2020, the crew of a Sikorsky S92A en route overwater to an offshore oilfield southwest of Stavanger received an engine 1 fire warning. They responded by shutting down the engine, deploying both fire extinguishing bottles, and eventually declaring a MAYDAY without taking all recommended steps to confirm an actual fire existed. They were aware that false engine fire warnings on this helicopter type had become a fairly regular occurrence, and when the warning persisted, they restarted the engine which ran normally. The flight was completed and made an uneventful landing on a platform close to the originally planned destination.

Flight Details

Aircraft

Type of Flight

Public Transport (Passenger)

Flight Origin

Take-off Commenced

Yes

Flight Airborne

Yes

Flight Completed

Yes

Phase of Flight

Cruise

Location

Approx.

120nm SW of Stavanger Airport

General

Tag(s)

En-route Diversion,

Inadequate Aircraft Operator Procedures

FIRE

Tag(s)

Fire-Power Plant origin

HF

Tag(s)

Inappropriate crew response - skills deficiency,

Inappropriate crew response (technical fault),

Procedural non compliance

EPR

Tag(s)

MAYDAY declaration

AW

System(s)

Fire Protection

Outcome

Damage or injury

No

Non-aircraft damage

No

Non-occupant Casualties

No

Off Airport Landing

No

Ditching

No

Causal Factor Group(s)

Group(s)

Aircraft Operation

Aircraft Technical

Safety Recommendation(s)

Group(s)

None Made

Investigation Type

Type

Independent

Description

On 20 October 2020, a Sikorsky S92A (LN-OMI) operated by Bristow Norway on a North Sea offshore passenger flight from Stavanger to the Ekofisk Kilo offshore oil and gas platform as BHL203 was approximately an hour into the flight in day visual conditions (VMC) when a left engine fire warning occurred. There were no secondary indications that a fire had occurred, but the engine was shut down and both fire bottles were discharged. However, the warning continued. Since the Ekofisk platforms were nearer than the nearest airport (Stavanger) it was decided to continue there. A MAYDAY was eventually declared, but since the warning had continued the crew believed it was most likely false. The engine was successfully restarted and the flight completed without further event.

Investigation

The occurrence was immediately reported to the Norwegian Safety Investigation Authority and a serious incident investigation was commenced with the combined voice and flight data recorder (CVFDR) removed and secured the same day. All data subsequently downloaded was of good quality and useful to the investigation. The 41-year-old captain had a total of 5,170 hours flying experience which included 3,795 hours on type. The 34-year-old first officer had a total of 3,495 hours flying experience which included 1,464 hours on type.

What Happened

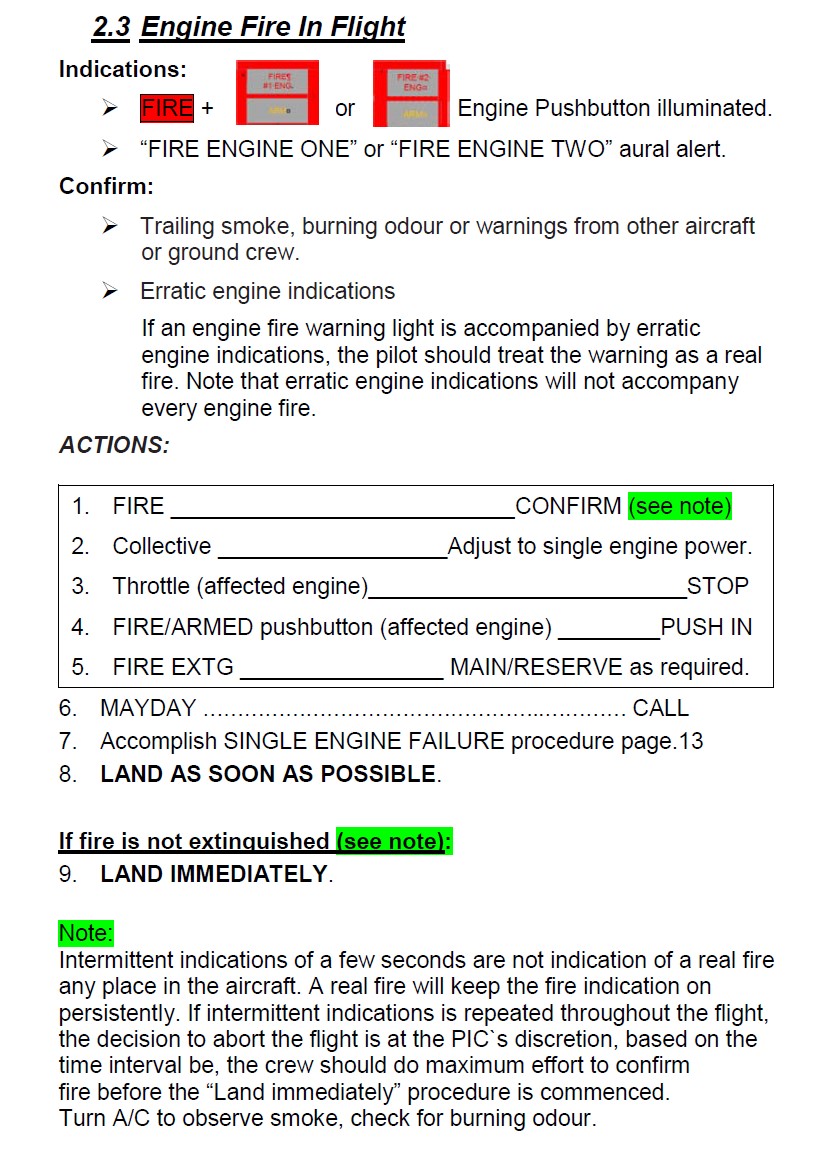

Just under an hour into the flight, an engine 1 fire warning occurred. The helicopter was equipped with two external tail-mounted cameras which allowed the pilots to view both engines, the main rotor and the main gearbox. These were checked but there was no sign of any fire or smoke and there were no other indications of possible engine fire in the form of irregular or erratic engine 1 indications. Had such indications been present, the Engine Fire in Flight Checklist explicitly instructed that a warning should be treated as real (although it was also cautioned that “erratic engine indications will not accompany every engine fire”).

However, the crew decided the engine 1 should be shut down. Twenty seconds after the waning had begun, collective pitch was reduced for single-engine operation, and the engine was shut down and the main fire extinguisher bottle was discharged. When the warning did not stop, the reserve fire extinguisher bottle was discharged, which meant that there were no more fire extinguishers available in the event of fire in the other engine or the auxiliary power unit (APU). The fire warning continued and the pilots discussed whether it would be better to return to Stavanger, which would take around 50 minutes or continue to Ekofisk, which would take around 20 minutes. They decided they would continue to Ekofisk - to either the flight-planned Kilo platform or the nearby Lima platform. They agreed not to ditch the helicopter and after considering whether to declare a MAYDAY, initially decided not to.

The crew noted that the engine 1 TGT (Turbine Gas Temperature) was low and considered that this may indicate that any possible fire would have to be external to the engine core. The warning continued and after it had been continuous for over three minutes, it was agreed that it was probably false. A further discussion on whether to declare a MAYDAY also occurred (but it was again decided not to do so) and it was discussed if engine 1 could be restarted before landing. After a further 1½ minutes of the fire warning (making a total of four and a half minutes), it was decided to declare a MAYDAY whilst continuing on track to the destination platform complex on the basis that they believed the engine 1 fire warning to be false.

After the fire warning had been continuously active for 14½ minutes, it briefly stopped before restarting and remaining active for another 4 minutes before stopping again. Half a minute later, engine 1 was successfully restarted and an uneventful landing on Ekofisk Lima followed 25 minutes after the fire warning had started. The engine 1 fire detectors and the two discharged fire bottles were replaced and the helicopter was released to service.

Why It Happened

The investigation report said “false warnings can be difficult to handle, especially if the checklists do not provide sufficient decision-making support (and that) there is no predetermined answer as to how to act in such situations." It noted that the crew had initially treated the fire warning as if it were real, shut down the engine and discharged both fire extinguishers into it--and then made decisions based on the assumption that the warning was false. The checklist below lists recommended ways of confirming whether the fire warning is real.

The Engine Fire In Flight Checklist used by the crew.

[Reproduced from the Official Report]

However, the crew had expected the warning to cease and when it did not, they decide initially to continue to Ekofisk on one engine. This was one of the final two checklist options ‘LAND AS SOON AS POSSIBLE’ or ‘LAND IMMEDIATELY.' However, the investigation noted that a MAYDAY was not declared until some time afterwards and considered that “a situation that leads to a single-engine offshore flight with passengers on board should imply an immediate MAYDAY call as stated in action 6 on the emergency checklist (since) the consequences of an engine fire can be severe." It was noted that although fire warnings must be taken seriously even if the fire warning system is prone to faults, there were no other indications that there was a fire on board. It was concluded that “a better understanding of the fire warning system” may have provided the crew with better decision-making tools.

In respect of continuing the flight rather than turning back, it was noted that whilst this had satisfied the ‘LAND AS SOON AS POSSIBLE’ option, it had at that point arguably increased risk in several areas:

- If there still was a fire on board the helicopter, it would not be a good idea to land on an oil installation.

- Landing on Ekofisk Lima with only one engine in operation would entail an increased risk.

- Restarting the engine could pose a safety risk.

- Could a possible fire be reignited when the engine was restarted? In such case, the crew would have had no possibility of extinguishing the fire.

Instead, it was noted that “the crew could have chosen to set course for land (and whilst) this would increase the flight time significantly, the search-and-rescue (SAR) helicopter based at Stavanger could have flown out to meet them and then followed the flight and observed possible secondary indications of fire and assisted during a possible ditching." This would have meant flying an extra 15 minutes over the sea before a rendezvous with the SAR helicopter, but the emergency aircraft would have landed on a runway without having to restart engine 1. The emergency aircraft also would have had the benefit of the airport rescue and firefighting services (RFFS) if required.

In respect of the continued flight it was noted that “although there was a high probability that the fire warning was false, it could not be ruled out that there had been a fire on board that had been extinguished by the fire extinguishing bottles.” The report said restarting engine 1 could, at worst, have initiated a new fire or caused a new fault that could have affected the safety of the helicopter.

Finally, the Norwegian Safety Investigation Authority was “surprised that Norwegian Civil Aviation Authority Norway (CAA-N) had not been aware of the high number of reported false fire warnings associated with the S-92 (given that) a fire warning system that triggers a high number of false warnings can pose a significant safety risk, in the event of both false warnings and real fires being misinterpreted." It was considered that since such flights “often take place over inhospitable seas and almost half of all landings take place on offshore installations....from a risk perspective the CAA-N should devote much (more) attention to this helicopter type." The Norwegian Safety Investigation Authority was “also surprised that Bristow Norway appears to have accepted the high number of false engine warnings” and noted that only after this serious incident did they “undertake a more thorough inspection of the fire warning system which found that corrosion in components within the fire warning system may have contributed to several of the false warnings."

The Safety Investigation Authority also stated that it now “believes that the high number of faults may constitute a breach of the requirements for certification of the fire warning system” and has accordingly “contacted the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) due to the high number of reported faults in the S-92’s fire warning system and they have responded that they will raise the issue with Sikorsky and the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

Finally, regarding crew actions, it was noted that the pilots “had not been specifically trained to handle false engine fire warnings” and the only checklist they had did not mention a continuous false warning so that they had to make decisions based on their own judgement. It was considered that Bristow Norway “should provide simulator training in how to handle false warnings” and that the engine fire emergency checklist must be revised to provide crews with a better basis for decision-making including but not limited to “use of the tail-mounted cameras to determine whether a fire is real.” The report also called for more clarity on the use of the phrase ‘LAND AS SOON AS POSSIBLE’ in an offshore situation.

The narrative Conclusion of the investigation was as follows:

False warnings have occurred on a number of occasions in the fire warning system on this helicopter type. This may explain why the crew first stopped the affected engine and deployed both fire bottles, before they concluded that the warning was false, restarted the engine and landed on the oil and gas platform Ekofisk Lima.

Safety Action

The engine fire in flight checklist was revised to provide better-presented guidance to pilots on to how it may be possible to distinguish a false warning from a genuine one and then re-issued on 10 May 2022.

The Final Report was approved on 2 November 2023 and published online the following day. No Safety recommendations were made.