UAV, near Sentosa Island, Singapore, 2024

UAV, near Sentosa Island, Singapore, 2024

Summary

On 19 February 2024, a relatively experienced UAV pilot lost control of a ST Engineering Aerospace DrN-355LS whilst operating it on a Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) flight about one mile over water from their Sentosa Island location. A brief interruption of the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) signal required the pilot to take control manually. But when the attempt to do so did not follow the correct procedure within the allowed five seconds, control was lost and the UAV ditched and sank and was not recovered. Improvements to pilot access to manual control reversion and related training were recommended.

Flight Details

Type of Flight

Aerial Work

Take-off Commenced

Yes

Flight Airborne

Yes

Flight Completed

No

Phase of Flight

Manoeuvring

General

Tag(s)

Deficient Crew Knowledge-systems,

Unmanned Aircraft Involved,

Delayed Accident/Incident Reporting

HF

Tag(s)

Inappropriate crew response - skills deficiency,

Inappropriate crew response (technical fault),

Procedural non compliance,

Pilot Startle Response

LOC

Tag(s)

Significant Systems or Systems Control Failure

AW

System(s)

Autoflight

Outcome

Damage or injury

Yes

Aircraft damage

Hull loss

Non-aircraft damage

No

Non-occupant Casualties

No

Off Airport Landing

No

Ditching

No

Causal Factor Group(s)

Group(s)

Aircraft Operation

Aircraft Technical

Safety Recommendation(s)

Group(s)

Aircraft Operation

Investigation Type

Type

Independent

Description

On 19 February 2024, automatic control of a DrN-355LS unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), serial number AC32-140, was lost during an overwater Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) demonstration flight from Tanjong Beach, Sentosa Island, to the Western Anchorage. The flight was carried out in autonomous mode and in day visual meteorological conditions (VMC). The UAV flew along a predetermined route approximately 164 feet (50m) asl with the unmanned aircraft pilot (UAP) manning the ground control station (GCS) at a remote site. The pilot had ability take over control of the UAV using the GCS, but when this did not happen in time, control of the UAV was lost.

The UAV involved in the investigated event. [Reproduced from the Official Report]

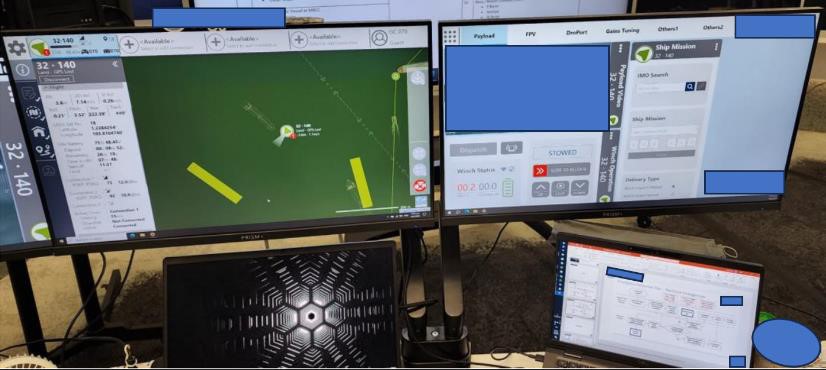

The Ground Control Station (GCS). [Reproduced from the Official Report]

Investigation

The event was reported to the Singapore Transport Safety Investigation Bureau (TSB) two days after it had occurred and an Investigation was commenced. The UAV involved was a six-rotor type with a 36.3 kg maximum takeoff weight (MTOW) and capable of flying up to 1,000 feet agl with a 3 kg maximum payload. The associated Ground Control System (GCS) comprised a laptop, two screens and a UAV controller. The laptop and screens enabled the UAP to carry out mission planning and preflight checks. All recorded flight data from the GCS was available for analysis. Regulatory requirements applicable to BVLOS operations (that the UAV shall remain within the specified area of operation at all times and that the flight time of the UAV over persons is minimised) were met.

The 44 year-old UAP held an unmanned aircraft pilot license (UAPL) (Class A & B Rotorcraft) and had 98 hours 51 minutes UAV control experience, of which 15 hours 53 minutes had been gained operating the type involved in the accident. The delay in notification of the event meant that there was no value in medical and toxicological examinations of the UAV pilot.

What Happened

The flight under investigation was the sixth flown since manufacture. Eight minutes after takeoff on the predetermined offshore route, a ‘POSITION X-CHECK FAIL’ error message appeared on one of the GCS Screens accompanied by an aural alert. At this point, the UAV automatically reverted to hover mode, maintaining its current altitude for five seconds to provide the pilot an opportunity to take manual control. This is achieved by selecting the ‘Hover-Manual’ command on the GPS screen.

When this option to take manual control had not been taken after five seconds, the UAV automatically reverted to the ‘Land - GS Lost’ mode and began a vertical descent to land at its current position. It was still possible for the pilot to assume manual control during the landing phase by selecting the ‘Hover-Manual’ command. However, the time in which this can be done depends on the height of the UAV above the surface below, which in this case was 164 over seawater. When the necessary action was not taken, the UAV, having drifted southwest from its hover position, landed on the water surface, sank and was not recovered.

The ground track showing positions of Santosa Island takeoff, loss of control and sinking. [Reproduced from the Official Report]

Why It Happened

The underlying cause of the loss of the UAV was the loss of Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) latitude data sent from the secondary GNSS receiver to its flight computer. Latitude and longitude position data are sent from both GNSS receivers to the flight computer five times every second. According to the UAV manufacturer, GNSS signals could be compromised by other transmissions using the same frequency bands such as radars and communication transmitters as well intentional GNSS jamming and spoofing.

Although the reason for the loss of a correct signal could not be determined, it was found that the latitude sent to the flight computer by the secondary GNSS receiver - 130.0793918° - was invalid because it was not within the permitted range for latitude and had created a position difference between the two GNSS receivers of 9,999.99 metres. This exceeded the maximum allowed, which could cause the UAV to “behave erratically." It was established by the UAV manufacturer that “although the unexpectedly large positional difference occurred only momentarily, the software calculated a positional difference of more than 20 metres that lasted for more than five seconds” which was sufficient to generate the ‘POSITION X-CHECK FAIL’ error message.

However, the immediate reason for loss of the UAV was that the pilot did not take control when autonomous operation was no longer possible. The investigation therefore examined the pilot training regime followed by the Operator. Initial type training had been conducted by the UAV manufacturer, which had been assessed by the state aviation regulator as meeting its requirements. The scope of this training was found to have included responding to a ‘POSITION X-CHECK FAIL’ error, with the training manual stating that this requires the UAP to engage the ’Hover-Manual’ flight mode. The UAV Operator’s ‘Flight Operations Directive’ was found to state that a UAP must:

- Complete an annual Final Handling Test (FHT) including all normal, non-normal and emergency procedures assessed to the required standard by a UAP Instructor from the operator.

- When holding a current FHT, maintain currency by operating the UAV for at least two hours within any three consecutive calendar months.

The UAP involved had last passed his FHT on 24 March 2023. They stated that they had only encountered the ‘POSITION X-CHECK FAIL’ error once and this was during a preflight check and not during a flight. They reported having been “startled” and by the time they recalled the appropriate response, the UAV was “already sinking."

It was noted that when this UAV type encounters an error, an aural alert occurs and appropriate response cues are displayed on one of the GCS screens. These consist of a pop-up message on the top right of the menu bar which remains for five seconds, an error indication attached to the UAV icon and an error message in the error log window.

The flight manual's ‘failure management’ section was found to list the actions to be taken by a UAP for each type of error that may be annunciated but this guidance was not displayed on the GCS screen because (according to the UAV manufacturer) these action lists “can be lengthy and may clutter up the GCS screen."

It was noted, however, that prior to the event under investigation, “the operator had, on its own initiative, compiled all the error types and the recommended actions for each type of error into an electronic document called the ‘Quick Reference Card’ (QRC)." This had to be opened on a separate laptop placed near the GCS for easy access and could be used to display the section of the QRC on recommended UAP actions for a particular error. In responding to the loss of control in the investigated event, the UAP stated that he had not referred to the QRC.

Key Findings from the Investigation were as follows:

- The transitory loss of a signal to the secondary GNSS receiver was probably due to external interference which caused erroneous GNSS latitude data to be sent to the UAV’s flight computer but how such interference could have led to erroneous GNSS data was not established.

- The UAV’s flight computer software had not been programmed to check whether latitude data received from the secondary GNSS receiver was valid or not.

- Although the erroneous latitude data from the secondary GNSS receiver only occurred momentarily, it resulted in a position difference that was larger than the UAV’s flight computer software had been designed to handle. When this situation arose, the software unexpectedly generated the ‘POSITION X-CHECK FAIL’ error message.

- According to the UAP involved, when the ‘POSITION X-CHECK FAIL’ error message occurred in-flight during the incident, they were startled and did not immediately assume manual control of the UA by clicking the ‘Hover-Manual’ command button on the Ground Control System (GCS) screen. By the time they recalled the appropriate necessary action, the UAV was already on the water and sinking.

- There were few opportunities for UAPs to be objectively assessed on their competency in all normal and non-normal procedures, including emergency procedures.

- The GCS screen did not display the recommended actions when error messages occur and although the UAV operator had compiled a Quick Reference Document (QRC) for use by UAPs, this was only available on a separate laptop. It was considered unlikely that a UAP would have time to locate the relevant procedure in the QRC when a ‘POSITION X-CHECK FAIL’ error message arises as there are only five seconds to react before a UAV begins an uncontrolled descent.

Safety Action taken as a result of the findings of the Investigation were noted to have been as follows:

- ST Engineering Aerospace as the UAV Manufacturer has updated the UA’s flight computer software so that it checks for invalid GNSS latitude and longitude data and has enabled the UAV’s flight computer to handle positional data from the primary and secondary GNSS receivers which has large-magnitude differences.

- Skyports Delivery as the UAV Operator has conducted refresher training for all its UAPs in handling all emergency procedures, in particular responding to the ‘POSITION X-CHECK FAIL’ error message.

Three Safety Recommendations were made based on the Findings of the Investigation as follows:

- that Skyports Delivery, as the UAV Operator, consider increasing the frequency of refresher training sessions that are to be conducted by a UAP Instructor. [RA-2024-005]

- that Skyports Delivery, as the UAV Operator, review the extent to which UAPs are required to commit to memory UAP actions that are time critical. [RA-2024-006]

- that ST Engineering Aerospace, as the UAV Manufacturer consider developing a method to make the recommended actions when an error is encountered readily available to a UAP. [RA-2024-007]

The Final Report was completed on 27 November 2024 and published online on 11 December 2024.