Engine Restart in Flight: Guidance for Flight Crews

Engine Restart in Flight: Guidance for Flight Crews

ENGINE AIR START IN FLIGHT

Discussion

This article provides general guidance for flight crews of turbine-powered aircraft on engine restarts in flight. Nothing herein supersedes aircraft-specific guidance in an operator's quick reference handbook (QRH), standard operating procedures (SOPs), or other official flight publications.

Under certain circumstances, pilots may elect to attempt a restart after an engine flames out in flight. Of course, if the situation makes it clear the engine is no longer airworthy, a restart is not advisable. Following a fire, overheat, oil loss, excessive fuel flow, or obvious mechanical malfunction, crews will secure the engine by closing off fluids and bleed air to minimize risk of further damage. Depending on the reason for the shutdown, this is normally accomplished by pulling the engine's fire handle, turning the ignition switch to OFF or STOP, or taking other steps to remove electrical power and close fluid valves. In the case of a turboprop engine, the condition lever will be moved to the FEATHER position.

Some aircraft manuals advise that if the engine flamed out for an unknown reason without obvious damage, crews may attempt a restart. Further guidance may state that if a condition such as heavy rain or turbulence is the suspected reason, crews may attempt a restart, ideally after the rain or turbulence has subsided. In some emergency situations, crews may need to attempt a restart even if they suspect damage, such as a flameout due to volcanic ash. (See the accident descriptions below.)

For many aircraft, the QRH makes the decision process easier by offering two different procedures: one for engine failure, which may lead directly to a a restart checklist, and one for engine fire, severe damage, or separation. In the latter case, of course, there will be no attempt at restart.

If an engine fails in level flight or in a climb, airspeed can deteriorate quickly unless the thrust lever for the operating engine is advanced. Crews in simulator training have been known to fixate on the air start and let speed decay. The pilot flying (PF) should prioritize flying the aircraft over assisting with the air start: Aviate, navigate, communicate.

In addition, crews should keep an eye on fuel balance. If the aircraft operates for long on one engine, fuel balance limits can be exceeded.

Engine Condition for Air Start

For most turbine engines, a good memory aid to help determine whether a restart is appropriate is the acronym V-O-R:

V: Vibration. Did you feel vibration before the engine failed? If the aircraft has vibration monitoring, did the instruments indicate out-of-limits vibration? If so, a restart may NOT be advisable.

O: Oil quantity. Does the oil quantity gauge indicate oil loss? If the aircraft has no oil quantity gauges, did the engine lose oil pressure? Is oil visible on the cowling? If there is any indication of oil loss, a restart is NOT advisable.

R: Rotation. Do the N1 and N2 gauges show that the engine core is windmilling? If there is no rotation at all, the engine has probably seized and will not restart.

In the case of turboprop aircraft, any propeller malfunction precludes an air start. A propeller that has lost hydraulic oil for pitch regulation could overspeed and potentially render the aircraft uncontrollable.

Air Start Limitations

Any given aircraft will have altitude and airspeed limitations pertaining to engine restart in flight. The QRH or other flight publications should include an airspeed and altitude envelope for windmilling starts and assisted starts.

Above a certain altitude, air starts will not be recommended. Typically, this altitude is 24,000 feet or higher. Below that limiting altitude, a chart or table of tabulated data will show the altitudes and speeds for windmilling starts, which rely on engine rotation due to ram air, and assisted starts, which use bleed air from an operating engine or from the auxiliary power unit (APU) to assist the starter. The data normally includes a minimum airspeed for air starts. This minimum speed, typically 250 or 300 knots, ensures adequate airflow to keep the engine rotating for a windmilling start.

If using APU bleed air to assist the start, as in the case of all engines flamed out, the APU's limiting altitude becomes a factor. With an all-engine flameout at high altitude, the aircraft may have to drift down below the maximum altitude for APU operation.

By the time the crew reaches this point in the decision-making process, they will have declared an emergency with air traffic control (ATC). ATC should be advised of the drift-down and any further crew intentions.

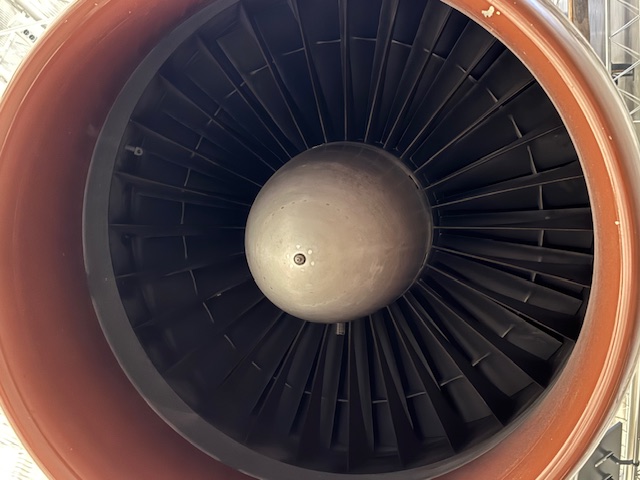

Pratt and Whitney JT3D engine on a Boeing 367-80 "Dash 80" (707 prototype). SKYbrary photo by Thomas Young, taken at the U.S. National Air and Space Museum's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center.

Air Start Procedures

With some aircraft, simply placing the thrust lever in the flight idle position will signal the full authority digital engine control (FADEC) to initiate an air start. If the aircraft does not have this capability, or if the auto-relight fails, crews will follow further QRH or SOPs to initiate an air start. This usually involves ensuring the above-mentioned altitude and speed limitations are met, then positioning the ignition and start switches for the air start.

If using bleed air to assist the start, the wing crossbleed valve may need to be opened unless the system's air start logic opens the valve automatically. Other bleed air loads, such as wing and engine anti-icing, may need to be turned off unless the system disables them automatically.

With turboprops, an air start depends on having adequate propeller oil to hydraulically move the propeller from the feathered position to the start position.

A successful air start will be indicated by rising turbine inlet temperature, oil pressure, and RPM. During this time, the pilot monitoring (PM) should watch for temperature exceedances and be prepared to terminate the start in the event of overtemperature, lack of oil pressure, or other malfunctions. (In most modern turbine aircraft, the FADEC will automatically terminate the restart if this happens. However, the crew should remain ready to intervene if necessary.) With many aircraft, the QRH will recommend letting the newly restarted engine warm up at flight idle before advancing the thrust lever, flight conditions permitting.

The final QRH steps for a successful air start will normally include directing the crew to move the transponder mode switch from TA ONLY back to TA/RA. (For an engine failure, procedures normally require selecting TA ONLY because an engine-out aircraft will not have the climb capability to respond to a climbing TCAS resolution advisory. With the engine restarted, this situation no longer obtains.)

Finally, even if the restart is successful and all systems look normal, the crew may want to consider a precautionary landing at the nearest suitable airport. Consulting with dispatch and maintenance via radio or ACARS can help inform this decision.

Emergency Air Start? Keep Trying

Three events, all involving Boeing 747s that entered volcanic ash, illustrate the importance of repeated attempts to restart failed engines in an emergency.

On June 24, 1982, a British Airways 747-236B encountered volcanic ash from an eruption of Mt. Galunggung, while flying 240 km southeast of Jakarta, Indonesia. The crew reported that St. Elmo's fire appeared on the windscreens, and "smoke" flowed from the floor vents. All four engines failed. According to the Aviation Safety Network (ASN), the aircraft began descending from 37,000 ft. After repeated attempts, the crew finally got engine #4 restarted at 13,000 ft, and restarted the other engines in succession. During efforts to restart the engines, the crew also dealt with pressurization loss, instrument malfunctions, and other complications. The #2 engine continually surged, so the crew shut it down. Despite visibility problems caused by ash abrasion of the windscreens, the crew made a safe emergency landing at Jakarta.

Approximately three weeks later, a Singapore Airlines 747-212B flew into volcanic ash from the same erupting volcano, while flying 110 nm southwest of Jakarta. According to the ASN report, the aircraft experienced multiple engine failures, and the crew landed on two engines at Jakarta.

On December 15, 1989, a KLM Royal Dutch Airlines flying near Anchorage, Alaska (U.S.) flew into what appeared to the crew as a normal-looking cloud at 25,000 ft. However, the cloud turned out to be volcanic ash from an eruption of Mt. Redoubt. Crew members reported seeing St. Elmo's fire on the windscreens and smelling a "sulphurous" odor. The ASN report says the crew added power to climb out of the cloud, but 10 to 15 seconds later, all four engines flamed out and the standby electrical system failed. After repeated attempts, the crew restarted the #1 and #2 engines while descending through 13,000 ft, and the other two engines restarted at 11,000 ft. The aircraft landed safety at Anchorage despite instrument malfunctions and other systems issues.

Although no one died in these events, all three were classified as accidents due to substantial aircraft damage.